This month has been a difficult month. Financially, the holiday season has not been kind to me. Most of the situations have not been of my own doing, but rather have simply been unfortunate facts or been losses on other people's parts, and thus mine. Rather than passing blame, though, I've focused on seeing these situations as learning experiences.

Even though being a freelance graphic designer is not typically considered a lower-middle-class type job, I've been forced to consider alternative forms of income. Not because I can't find work as a designer, in fact (I have enough to keep me occupied and afloat), nor because it is not in demand. It is simply because the work I do is actually too expensive for most people. And even though I do not charge really what the lot of my work is worth (not to sound like I have a big head, but it's actually what most people close to me tell me personally), what I do charge does not really cover my cost of doing business in the long term. Yet, even if I did charge a more "typical" freelancing rate, I wouldn't probably be able to take on the kind of work I have already (it would be too expensive for most of my clients). It is a kind of catch-22.

Part of this is the economy, part of this is the nature of Tucson itself and the city's economic climate. Other factors may be part of it though—the fact that I am a relative newcomer; that I have, frankly, a limited amount of connections (though growing).

But whatever the case may be, I try not to dwell on those things. The fact that I am part of a subsection of economic society that I would call the "lower-middle-class" has allowed me a bit of time to reflect on how other people live, or are forced to live, with a different kind of standard of living, especially in terms of finances. I was shielded from the economic downturn back on the East Coast. Here, it is no longer the case. Now the odd realities of this subsection come to the forefront: it is easy to slip through the cracks of this country, which is not based on religion, nor democracy—yes, you read that. And I'm fairly convinced by it. Rather, the United States is based on Capitalism.

Is it really that far fetched?

Maybe it's too strong a statement. But it's just a strong statement, I think, when ones close to you cannot afford health insurance, yet are too "rich" to afford food stamps. Or your close friend, who is a diabetic, does not benefit from the current options for health insurance as they are, since they cost them about as much as the medication and doctor visits would alone. Only the obviously socialist and Unamerican health care reform plan would actually improve her chances of making ends meet—and thus, in her case, keeping her body functioning properly.

The logic of capitalism is so simple, it is enticing: those who work hard enough will succeed. Those who do not work, or are not successful at their work, will not succeed. It is a romantic ideology, and carries with it a kind of snobbery. It assumes that, regardless of how much or how hard a person's work is, if it does not succeed given the conditions, it deserves to fail. It hinges on that clause "enough", and does not define the end goal beyond the vague word of "success". And it turns a blind eye to the ratio of work between the one who can lift a finger to invest and the one who must break their back to make their family's bread.

This inherent blindness is something that I think is reflected in Michael Moore's latest film, Capitalism, A Love Story. Not that I put a lot of faith in Michael Moore and his work—some of his latest films I think have been the work of elaborate fact weaving as much as they have been muckraking. But this one, which I saw months ago now, is echoing strangely these weeks as I watch both myself and my friends struggling to make their ends meet. Some might blame them for being artists in a world that does not favor the artist as an economic entity.

Well, I'd say that's a very capitalistic response. And, instead of concede it, I'd rather blame that response with a second blindness—ignoring the inherent value of the artistic consciousness in a culture that is more and more starved for meaning. And if you're doubtful of such a starvation, just visit the spiritual self-help section in the closest bookstore. I bet it'll change your mind. That response to artistic culture in a capitalist society can be compared to the same mentality I heard once evoked by an American man, only a few feet in front of me, when I was visiting the Louvre in Paris. He said, while looking at the classic paintings of Greek heros and Old Testament prophets: "You'd wonder if they all must have been naked back then!"

I would have laughed if he had not said it seriously. He couldn't, or didn't try to understand why it was worthwhile to dedicate your time to understanding the visual beauty of—and that which is underneath—the human body. I'd wonder if he'd say the same thing if he was walking through the Erotica convention in Los Angeles, since, after all, "they're all naked." Funny, that most porn stars seem to make a great deal more money than most painters. By the laws of capitalism, pornography must certainly be more valid or "viable" than art. There's no question of what it does to culture, society, the play of gender roles and relationships. Odd, that many social conservatives are also fiscal conservatives. I wonder how those two schools of thought may inhabit the same brain, and suppose that they each can happily coexist. If the institution of marriage is in trouble, why not get rid of the porn industry, which harms so many male minds and female bodies, and, by any typical measure of social conservatism, obviously dissolves the values that hold society firm. Of course, industries like that are too profitable. One puts their money where their beliefs are, don't they?

It's the irony of our culture, and how it plays out in those whose lives are less fortunate, or maybe just willing to make more sacrifices than the average. Yet at the same time, I realize that I am by no means unfortunate. In some places on this Earth, the machine I type these words on could feed a whole family for a year, perhaps. Just as I can't imagine living the life of a successful capitalist like Dick Cheney or Alan Greenspan, neither could a poor Sudanese woman imagine living the life I lead.

And there is another irony—the sad irony of our world. And as I remember how lucky I actually am, I'm thankful that this short stint in hard times can teach me what the value of ten, twenty, thirty dollars actually are. Hopefully the lesson will be strong enough that I can remember the way that other people must live, and that they cannot choose otherwise even if they wanted to (unlike me). Hopefully the rest of the world can gradually realize this—and it can put behind its comfortable, familiar ideologies of ethics and how economics "justify" it.

This Blog Has a New Address

16 years ago

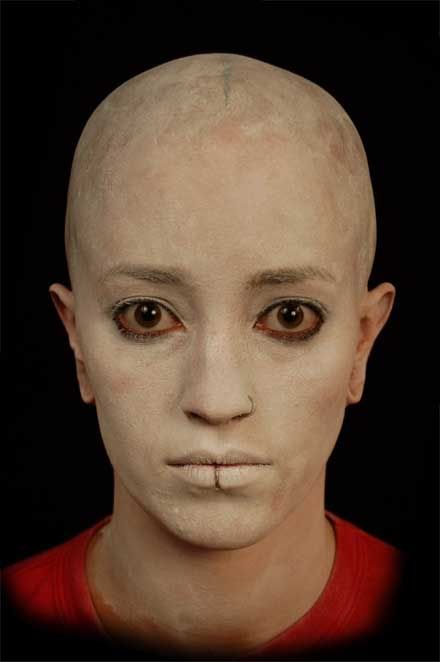

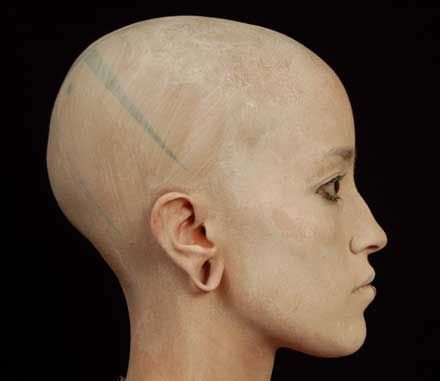

I saw Negypt twice this weekend. I made it a point to do so, in fact, because it took me two times to actually collect my thoughts on it. The first time I sat in the front row, the second I sat almost at the back, so that I could see others' reactions.

I saw Negypt twice this weekend. I made it a point to do so, in fact, because it took me two times to actually collect my thoughts on it. The first time I sat in the front row, the second I sat almost at the back, so that I could see others' reactions.